Main Content

The Reorganisation of Municipal Integration Work Using the Examples of Schwerin, Halle and Cottbus

Since 2015, eastern German cities have increasingly become new destinations for international migration. The majority of immigration took place in the large housing estates, which still had larger vacancies in the housing sector. Here, the proportion of immigrant population rose sharply, which posed major challenges for municipalities and urban civil societies. As part of the “StadtumMig” project, the IRS examined the reorientation of municipal integration work from 2015 onwards. The researchers were able to show that the municipalities were able to quickly establish their own structures and cooperation networks, but that their stabilisation remains difficult.

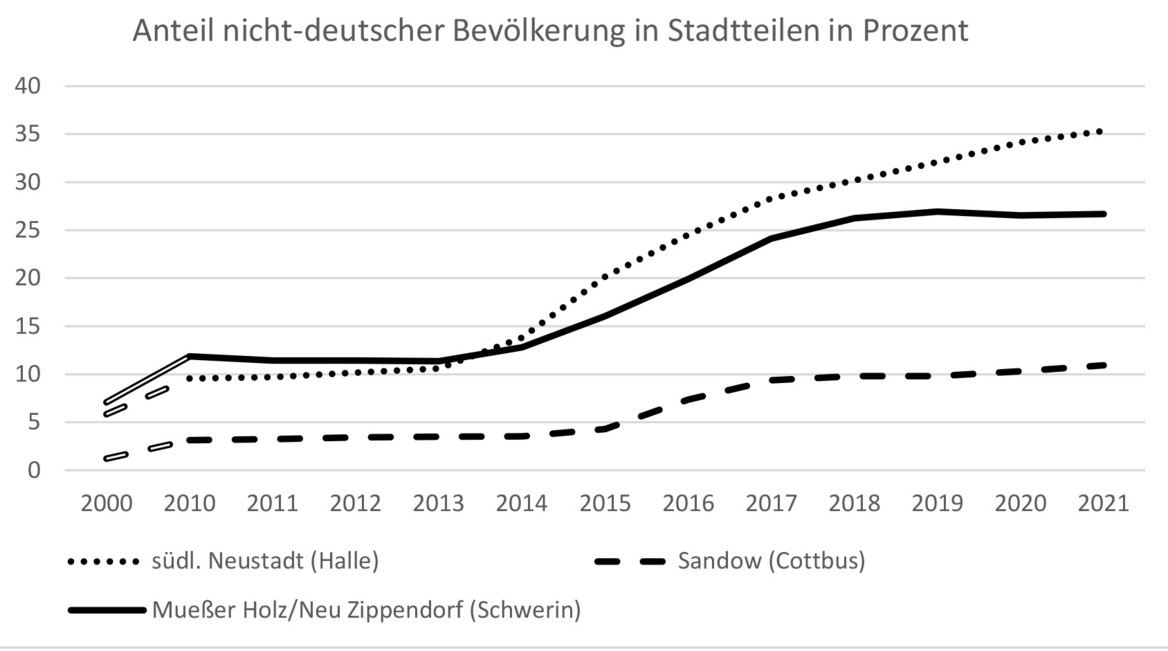

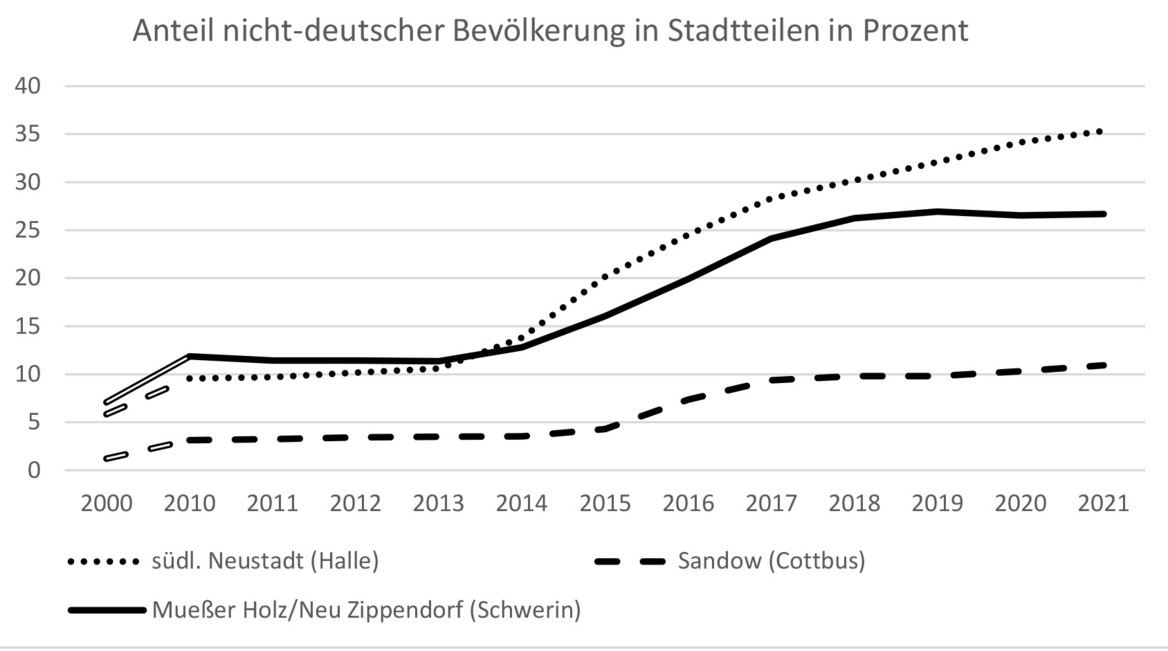

Eastern German cities have established themselves as places of arrival at the latest since the strong influx of refugees from 2015 onwards. The change was particularly noticeable in cities with large housing estates, which had previously been heavily affected by migration and thus vacancies. Such cities often took in more refugees than the Königstein Key – the nationwide distribution key for refugees – would have provided. As a result, in some large housing estates, such as Halle-Neustadt and Schwerin-Mueßer Holz, the proportion of migrant population rose from a very low starting level to up to 30 % in a short time. As a result, these municipalities have to cope with major integration tasks. For the cities, this development had positive and negative effects. On the one hand, they were able to stabilise their population figures, especially in the large housing estates; the new residents contributed to a rejuvenation in the neighbourhoods and also to a reduction in the housing vacancy rate. On the other hand, the demographic change also increased the deficits in the neighbourhoods, including the infrastructural undersupply.

The recent influx of refugees from Ukraine suggests that 2015 was not an isolated case and that municipalities as a whole must prepare themselves to be able to react quickly to immigration. So what can be learned for the future from the 2015 immigration situation? How do municipalities need to be positioned for this?

Researchers in the joint project “StadtumMig – From Urban Redevelopment Focus to Immigration Neighbourhood? New Perspectives for Peripheral Large Housing Estates” in three large housing estates in the East German partner cities Schwerin, Halle and Cottbus. Researchers from the IRS have specifically investigated the transformation of municipal administrative structures and approaches, especially in the integration and urban planning offices in the three municipalities. In order to grasp the scope of the changes, they compared municipal concepts of action, analysed documents and conducted numerous expert interviews with employees of the administrations, the regular services, in the projects of social organisations as well as with volunteers of various initiatives and self-organisations of migrants.

Three central findings can be formulated on the basis of these investigations:

- An alignment of values and orientations in municipal integration work had already taken place to a large extent in the years before 2015, namely towards an understanding of integration as a process of change in society as a whole.

- Regardless of this, however, the three project municipalities have taken very different paths in developing new administrative structures since 2015 and 2016.

- The involvement of volunteers plays a major role in the implementation of integration tasks.

From improvisation to strategic coordination

The reorganisation of municipal integration work after 2015 took place in several phases and varied locally. At the beginning, it became clear that existing structures had reached their limits. In Schwerin and Halle, for example, it became apparent that the existing position of integration officer was no longer sufficient to adequately address the situation. In the first phase, which was about coordinating the initial reception and accommodation of the increasing number of refugees in 2015 and 2016, new key figures established themselves in the administrations. In Schwerin it was the newly appointed head of social affairs, in Cottbus the new coordinator for asylum in the social affairs department. They were able to draw on internal administrative, interdepartmental working groups in the municipalities. After about a year, the experiences with the arrival process led to a second phase in which visible, but in the cities studied very different, reorganisations of the municipal structures in the area of integration took place.

In Schwerin, the existing structures were reorganised by adding two pilot posts to the office of the integration commissioner and assigning it to the social department. The new head of department pursued a comprehensive conceptual integration of integration work with the municipal compulsory tasks in the social sector, e.g. with youth social work or day care planning. The restructuring made it possible to link some of the integration tasks with the current tasks in these areas and to finance them partly through this.

In Halle, a new structure was established to improve governance – the Service Centre for Integration, which was placed under the Lord Mayor's office. The new centre gave integration work a high visibility and can be read as the city's commitment to taking on the tasks. In addition to the management position, the integration officer and a team that managed the decentralised accommodation of the refugees were located here. The later integration of other municipal commissioners and democracy promotion into the centre not only enabled better cooperation between the commissioners, but also a consolidation of the new structure.

In contrast to Schwerin and Halle, the management in Cottbus was bottom-up. The coordinator for asylum organised conferences with committed people and employees of social organisations and projects in all districts affected by the influx. The focus was on the challenges of working with refugees, the need for support from the administration and networking between the actors. The result of these conferences was a list of demands that formed the basis for negotiations with the Brandenburg state government on the design and financing of migration social work in Cottbus. In addition, external funding was placed with the coordination office, so that a new structure was also created in Cottbus - the department for education and integration with sixteen employees, which was subsequently integrated into the mayor's office and upgraded to a specialised service.

The very different forms of reorganisation of integration work in the cities depend on various factors, firstly on the key figures established in the process and secondly on their possibilities to secure the new structures financially. This is because integration work is still a voluntary municipal task, and cities have to renegotiate the funding for it with the state governments again and again. This often makes it very difficult for municipalities to establish long-term, new positions or structures to manage integration tasks in their administrations.

Integration work in the neighbourhood – asymmetrical cooperation

In the implementation of integration tasks, the municipalities are also dependent on grants and project tenders from the Länder, the federal government and the European Union, resulting in a more temporary and project-based financing of municipal integration work. One way to compensate for this regularly changing funding is to involve volunteers in integration work. Of course, this also brings a great advantage, namely the participation and co-creation of the integration process by the citizens, which also supports the opening and transformation of society as a whole. In the research of the StadtumMig project it became clear that different forms of cooperation with the voluntary sector have been established in the city administrations. Schwerin and Halle, which already had very well established integration work before 2015, have long-standing horizontal structures for cooperation: the integration networks, which are led by the integration officers. The issues of integration work are discussed here in various thematically organised working groups. Cottbus was at the beginning in this regard in 2016, but was quickly able to establish a horizontal way of working due to numerous active initiatives, although this has not yet been institutionalised in this form. Cooperation here takes place in district or specialised conferences.

In the example of the three cities, it was observed that both integration networks and event-related cooperation in conferences are suitable forms for jointly addressing the tasks in the immigrant neighbourhoods. However, there were clear differences in the way administrations approach and involve volunteers. In Schwerin, attention is paid to compensating for the perceived deficits of volunteers, such as – from the administration's point of view – a lack of efficiency and parallel activities. In Cottbus, on the other hand, volunteers are involved in the joint preparation of negotiations with the state or city government about finances and new strategies. The Cottbus model is thus based more on the idea of an alliance with the actors in the neighbourhood, whereas cooperation in Schwerin in the past has shown quite dirigiste traits.

The British economist, sociologist and political scientist Bob Jessop, who has studied the challenges of governance in vertical and horizontal networks, points to the difficulties of coordinating different types of actors in horizontal networks. These are characterised by different working methods, motives and resources, which also always characterises an asymmetry of power in the networks. While the main office (in this case administrative staff) focuses on objectives, effectiveness and synergies, the voluntary work is about mutual support and empowerment. The findings of the StadtumMig project suggest that more top-down organised coordination models can be very efficient, but that there is a danger of not respecting the voluntary nature of voluntary work enough and limiting its decision-making and organisational possibilities. This can break down the asymmetries in horizontal networks, which would impair cooperation.

In summary, the inter-municipal comparison in the StadtumMig project suggests that municipal administrative structures in the field of integration can be organised very differently. However, it is important to have reliable funding in order to prevent an endless loop between the situation-related development and dismantling of structures, positions and projects. Integration work that is designed horizontally, as cooperation with citizens, can promote a sustainable process of opening and transformation in urban society.