Main Content

“Villa neighbourhoods are largely overlooked, especially when it comes to their social significance and long-term development.”

Interview with Eva Maria Gajek

Many people are familiar with the concept of “good addresses”. But how did they become what they are today? The research project “RichMap – Where the Rich Live” examines German villa districts throughout the 20th century. Eva Maria Gajek, historian in the IRS Research Area “Contemporary History and Archives”, is one of two project leaders.

Dear Ms Gajek, the project you have been leading together with Kerstin Brückweh since May is called "RichMap". What does the term mean – a map that is rich or a map of the rich?

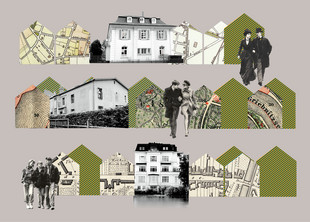

Both! The title “RichMap” plays on this ambiguity. It is a map on which we want to trace the transformations of villa districts in East and West Germany in the 20th century. These areas are often associated with wealth in the public eye. But we want to take a closer look at these places and examine how certain neighbourhoods became “good addresses”, how they were able to maintain or lose their exclusive status, what continuities and breaks can be seen in their history – and what this tells us about social inequality, urban development and the symbolic meaning of wealth. However, the map should not just name places – that would also be difficult in terms of data protection – but rather provide a view of these neighbourhoods from different perspectives and using various sources: from photographs and audio files to archival documents and various maps to social data, enriching them and thus making them “dense”, i.e. a rich map.

Why is it important for us to focus on affluent neighbourhoods, and what is new about this?

Research has so far focused primarily on large housing estates, working-class neighbourhoods and marginalised districts. These were often labelled as political “problems”, partly as a way to understand and address social inequality in the present. Villa districts are largely a blind spot – especially when it comes to their social significance and long-term development. Although we now know quite a lot about their origins in the 19th and early 20th centuries, we know surprisingly little about their transformations over time. This is particularly interesting in view of East German villa districts, which underwent two profound upheavals: first through socialist conversion in the GDR and then through the reorganisation of ownership structures, investments and symbolic upgrades after Germany’s peaceful revolution in 1989. These processes have hardly been researched to date, even though they raise key questions about property, spatial planning and social inequality. This is because villa districts should not only be understood as places where people live, but also as places where real estate ownership and social capital can perpetuate structures of inequality in the long term. However, the East German example also shows that these spaces, which at first glance appear to be strongly associated with continuity and homogeneity, are also characterised by change and heterogeneity, and it is particularly interesting to explore this.

RichMap brings together historical and social science research. What is the interest of each side? And what is the added value of cooperation?

Historical science asks how villa districts developed historically, which actors were involved, and how attributions of meaning have changed over time. The social sciences in this project are more interested in contemporary social dynamics, including neighbourhoods, mechanisms of exclusion, and symbolic spatial production. By combining the two, we can link historical depth with contemporary analyses. This is because many of today's structures of inequality have historical roots – who was allowed to live where, who was allowed to keep or lost property, has long-term consequences for urban spaces and social participation. The combination of history and social science therefore also helps to better understand current social divisions. A central connecting element is the map – not only as a visualisation tool, but also as a methodological instrument. We ask: How can wealth be mapped, and is this even possible? Which stories and meanings become visible as a result, and which remain invisible? The development of so-called thick maps is therefore a shared space for methodological innovation in which both disciplines work together productively.

In this project, the IRS's research focus "Contemporary History and Archives" cooperates with numerous other groups and institutions. How would you describe this network and what does each side contribute?

Our network is not only interdisciplinary, but also international. Historians, urban researchers, sociologists, geographers and mapping experts work together – from Germany, but also from the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Australia and Italy. This international perspective helps us to better understand the special features of German urban space, its villa districts and its culture of wealth, and to classify them comparatively. Collaboration with experts from the field of citizen science is also particularly important to us. RichMap not only wants to analyse, but also to make visible and promote exchange with urban society. The question of how we can present knowledge about social inequality and wealth in such a way that it can be discussed publicly is central to our work. By combining scientific analysis with participatory approaches, we hope to open up new perspectives on familiar urban spaces.

What exactly does the team at the IRS do?

At the IRS, we bring together methodological and theoretical perspectives on space and society. Kerstin Brückweh and I developed the conceptual foundations of the project and are now continuing this work. We coordinate the network activities and are working in particular on the question of how wealth can be mapped historically and spatially – in the form of so-called "thick maps", i.e. dense, contextualised maps. This is also the subject of Lilli Rast's dissertation on the methodology of these thick maps. In addition, I will be writing a book myself that deals with the transformation of neighbourhoods over the long term. I am interested not only in how the upheavals of the 20th century and systemic changes affected the space of the villa district, but also in how society recorded knowledge about this space, marked it and drew boundaries, and how very different spaces could become part of an idea of "the villa district". In parallel, questions of integration and communication within urban societies – i.e. approaches to citizen science that we are developing to fit our specific needs – are also central and are being advanced at the IRS with various partners.

How can one imagine such a "rich map" in concrete terms – has there ever been one before?

A rich map is more than just a simple map showing the locations of villas. It combines historical sources, socio-economic data, subjective narratives and media representations – visually and interactively. Such dense maps of villa districts are rare to date. We see them as a methodological innovation that goes beyond classic GIS mapping and involves various actors in the production process. However, they have already been tested in various other contexts, which is why those who have already worked with them and methodically addressed the challenges are also part of our network.

What are the first steps?

We have begun mapping historical property and address data from around 1900 in order to identify the first "good addresses". This early data provides us with a basis for tracking the development of individual neighbourhoods over time. At the same time, we are supplementing this with additional sources from archives – for example, on relocations, ownership structures or family networks – and also mapping infrastructure. This is currently being done primarily for individual case studies such as Potsdam and Cologne. Initial interviews with residents and experts are also being planned. Step by step, a dense map is emerging that shows more than just street names: namely, social dynamics and long-term changes.

When will there be something to see?

That's not an easy question to answer, because alongside our work on content, we also have to clarify key issues relating to data protection, data ethics and anonymisation. We are very carefully considering what information we can make publicly available – and what should remain internal, as a scientific analysis tool, also to prevent misuse. Nevertheless, we want to make the development process as transparent as possible. We will therefore publish and present initial interim results during the project period – for example, in the form of lectures, texts or workshops. Dialogue with the urban population is also important to us: we are planning formats to engage in conversation with citizens and incorporate their perspectives. We hope to be able to present the first publicly visible results – particularly in the form of mapped data and analysis results – at the end of 2026.

You yourself have already done a lot of research on elites, inequality and wealth. What motivated you to do this, and what does this project mean to you?

I have long been interested in how social inequality not only exists in fact, but how it becomes visible – in debates, in urban spaces, in self-attributions and attributions by others. Villa neighbourhoods are a fascinating subject of study precisely because these places are associated with ideas about wealth and have always been the location of "the rich", even though nothing specific is known about the actual financial circumstances of the residents. RichMap brings together many of the themes that have accompanied me in my research: questions about elites, space, symbolic power and historical continuity. For me, RichMap is also an opportunity to make history socially relevant. At the same time, I find it particularly appealing to implement this project at the Leibniz Institute for Spatial Social Research in Brandenburg. The IRS brings a distinctly socio-spatial perspective to social transformations and has an established network of political, municipal and civil society actors. This environment makes it possible to discuss the social and political significance of property, space and inequality – especially in the East German context with its German-German history of property relations – in dialogue. At the same time, with its "Cooperative Excellence" funding line, the Leibniz Association provides RichMap with a framework in which these topics can be addressed in an interdisciplinary manner and in exchange with other institutions. All in all, I find this a very stimulating environment.

Against the backdrop of your research, how do you view the public discourse on wealth here in Germany?

The discourse on wealth in Germany is full of ambivalence: wealth is a taboo subject, but at the same time it is omnipresent. The "rich" are a projection screen and a target, but rarely the subject of differentiated analysis. This is precisely why historical classification and empirical research are needed. I hope that RichMap can also contribute to objectification here – not least through other forms of differentiated analysis.

Thank you very much for talking to us!