Main Content

Who rents and how? A Housing Economics View of Large East German Housing Estates

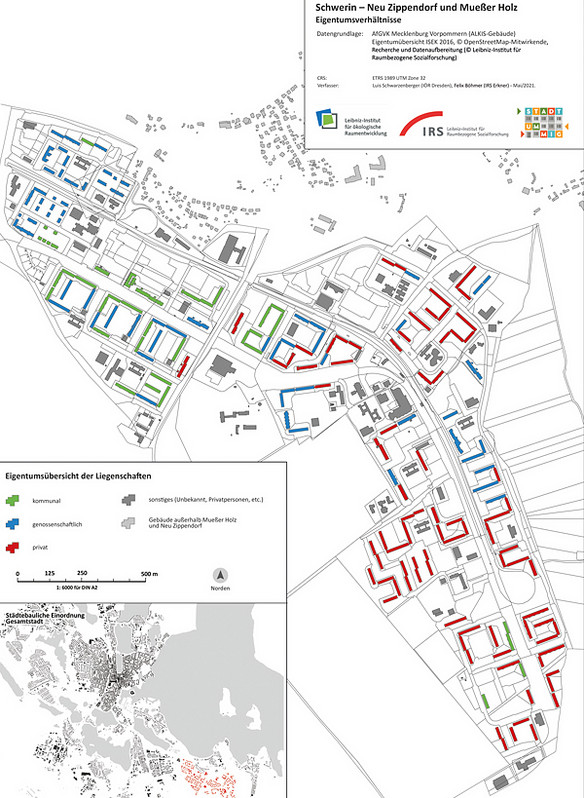

What role do housing ownership relationships play in the development of large housing estates? How do they influence their social structures and development prospects? The IRS investigated these questions in the southern Neustadt in Halle (Saale) and on the Dreesch in Schwerin, among other places. It turned out: East German large housing estates have experienced a reshuffling of the homeowner structure in recent years. Commercial investors have acquired considerable parts of the housing stock and have become a structure-determining factor alongside municipal and cooperative owners. The consequences are very differentiated.

As part of the StadtumMig project, the respective planning histories of selected large housing estates were reviewed, documents (e.g. planning documents and annual reports) were analysed, and interviews were conducted with administration, the housing industry, urban planning and other actors. The aim was to understand the different perspectives on the transformation of large housing estates. Ownership structures and housing business models formed a separate research module.

In retrospect, the path to today's ownership structure of large housing estates in East Germany can be understood as a sequence of three waves of sales: The first wave can be traced back to the Old Debt Assistance Act (AltSchG) of 1993, which obliged “old debt-burdened” municipal and cooperative housing companies from the GDR to privatise one sixth of their holdings. In the GDR, housing companies had taken on debts with the GDR state bank, which, however, had no factual significance for their housing activities. With the privatisation of the GDR state bank, "virtual" debts became real debts. The governing coalition of CDU and FDP decided to reduce the debts through a state old debt redemption fund as well as a lump-sum partial privatisation of the stock. Even then, buying up these flats became a playing field for “knights of fortune and prefabricated housing hasards”, as the news magazine “Der Spiegel” wrote in its 11/2000 issue. Almost without exception, these had to file for bankruptcy after a few years. The affected stocks thus fell into the receivership of the lending banks and were sold on several times in the following years, often in “packages” with other investments such as wind turbines or shopping parks.

A second wave of sales began in the 2000s. At that time, East German cities were confronted with population losses that had taken on dramatic exceptions in the large housing estates. One consequence of this situation was a sharp drop in property prices in the affected areas. Interview partners told us that in the 2000s discount purchase prices of 60 euros per square metre for an unrenovated prefabricated building were normal. The properties privatised in the 1990s were shifted back and forth between different owners over a period of about ten years, with speculative business models dominating. In addition, there were further “private treaty” sales by municipal and cooperative companies that needed liquidity in the difficult market situation.

Since the 2010s, privatisation of municipal and cooperative housing has been a thing of the past, so that hardly any new stock comes onto the market. This leads to concentration processes in which portfolios are sold on from one financial investor to another, companies merge, or portfolios are combined in specialised sub-companies and sold on. Profits are achieved primarily by exploiting economies of scale (profitability through mass), by insourcing (the handling of janitorial, repair and other services through own subsidiaries that are trimmed to extreme cost savings) and, where possible, rent increases. This development can also be observed paradigmatically in the city districts studied. For example, in the southern Neustadt in Halle (Saale), properties acquired in the 2000s by a relatively small company specialising in insolvency buyouts were taken over in the 2010s by the listed company Grand City Properties, based in Luxembourg, and finally sold on to the Swedish Heimstaden Group in 2021. As a result, the list of owners in both districts now reads like a Who's Who of the financialised (i.e. driven by investors' expectations of returns on the capital market) housing industry in Germany.

With the rise of listed, highly profit-oriented housing companies, three distinctive housing industry models can now be found in large housing estates in eastern Germany. They sometimes differ significantly in how they allocate housing and how they deal with their property portfolios.

Municipal housing companies

In general, municipal companies in Germany are often called upon by their municipalities to assist in the fulfilment of compulsory municipal tasks. This includes the provision of housing for groups of people who cannot provide for themselves on the market, such as recipients of transfer payments and asylum seekers. As a result, municipal housing companies usually provide a disproportionate amount of housing for low-income groups and groups discriminated against in the housing market. The fact that the companies' portfolios are spatially concentrated in large housing estates already leads to an increased spatial concentration of socially disadvantaged people in these estates.

Cooperatives

In addition to the municipal enterprises, the housing cooperatives represent a second pillar of housing provision in the large housing estates in East Germany. Due to their specific legal construction, they often have a tendency towards structural conservatism, where the boards of directors do not bring proposals to the general meeting that they expect to be rejected by the majority of the members. This is particularly true for the housing of stigmatised population groups. In addition, applicants for housing in cooperatives have to subscribe to cooperative shares when renting a flat. This is a considerable problem for people on transfer payments, as these costs are rarely covered by the job centres or the foreigners' offices. As a result, the proportion of these groups of people in cooperative housing is far below average.

Private renting

The rental policies of private, often capital market-driven housing companies are extremely heterogeneous. In addition to companies that almost never rent to recipients of transfer payments and people without German citizenship, there are also companies that focus their rental business on precisely these groups. In this case, low purchase prices, high occupancy rates, low management costs and state-guaranteed rent payments are combined into a successful rental model. Unlike municipal and cooperative companies, locally operating property management companies are closely integrated into global corporate strategies in which the development of individual locations plays only a subordinate role. They often have tight targets in terms of rental income and little scope for investment. As a result, they often focus on ensuring high occupancy rates and are very competitive in the market to do so. There are reports of the “99 euro flat”, the distribution of Arabic-language flyers in front of refugee accommodation and a waiver of debt-free and creditworthiness checks. The following quote from an interview with a property management company succinctly reflects this orientation: “Somewhere in a distant location sits a lettings person who processes the statistics. And to be honest, he doesn't care whether we put up a headscarf or a Hartz IV recipient. The main thing [...] is that the terminations that come in are compensated for by new contracts [...]. ”

As a result of this rental practice, households that are discriminated against elsewhere or can only afford the cheapest offers due to their income situation are often still most likely to find accommodation in the flats bought by financial investors. As with the municipal companies, this leads to an increased concentration of poor households in the corresponding stock.

The overall picture is differentiated: On the one hand, there are considerable differences between individual landlords. Above all, the cooperatives are “anchors of stability” in the areas. However, this also goes hand in hand with a weaker commitment to providing low-income groups with housing. This task is largely taken over by the municipal companies and some private landlords. As a rule of thumb one can state: The higher the share of municipal and/or private landlords in a large housing estate, the lower the social status. The losers are primarily the areas where demolitions in the context of urban redevelopment and privatisation of municipal and cooperative housing have been concentrated in the past. Extreme concentrations of poverty have developed here in a very short time. The neighbourhoods studied in the StadtumMig project indeed belong to this group.

The great importance of commercial housing companies for the strong concentration of financially weak and/or migrant households in large housing estates has so far been neglected in discussions about the planning and urban policy control of the social development of large housing estates. The relevant networks are almost exclusively made up of municipal housing companies and cooperatives that work closely with politicians and have been involved in processes of cooperative neighbourhood development for a long time. Commercial housing providers have so far been a “blank spot”. They cannot be reached through purely voluntary cooperation, but at the same time they play a key role. The question of how they can be involved in efforts to develop large housing estates in a socially sustainable way must be asked more actively.