Main Content

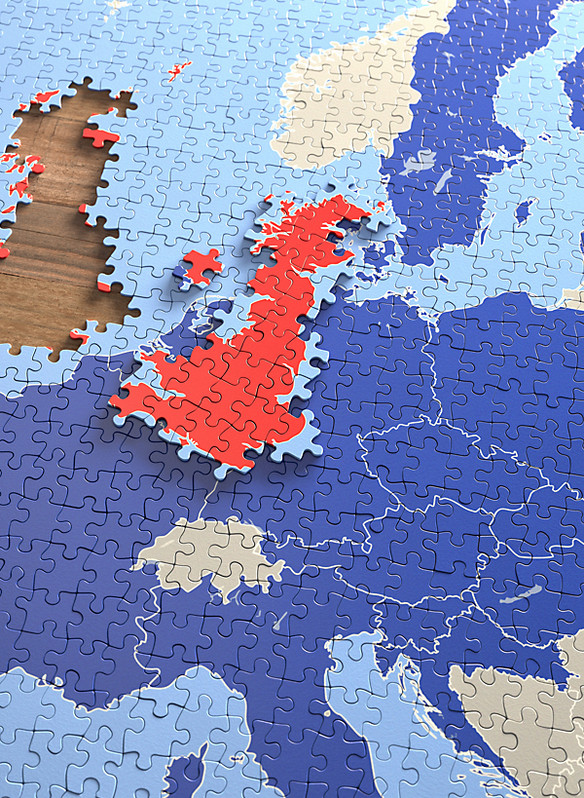

Brexit and Corona: The Double Crisis of Universities

British universities are currently being hit by a double crisis: Brexit is jeopardising their access to the European Research Area and thus to EU research funding. At the same time, the COVID19 pandemic is jeopardising an important pillar of the globalisation of higher education, which is being pushed by France and the UK in particular: offshore campusses that attract affluent, highly mobile students. Universities are responding with adapted strategies and even taking advantage of the new opportunities offered by the crisis.

Brexit is currently presenting British universities in particular with funding problems in several respects. It is still unclear to what extent universities in the UK will participate in the EU student exchange programme Erasmus or in joint European research funding in the future. What will happen to academic staff from EU countries if visa regulations become stricter? Will British universities remain attractive to European students? Until now, they have had to pay a reduced tuition fee, just like British students. Now they will be subject to the much higher rates for "international" students. And what will happen to research funding when the attractive funding programmes of the European Union are no longer accessible to UK-based researchers?

The Leibniz Junior Research Group "TRANSEDU" at the IRS investigates internationalisation strategies of universities, especially the establishment of offshore campuses. During the field research, it also gained insights into the effects of Brexit.

Brexit: Strategies against Disengagement

The loss of access to the European Higher Education Area and the European Research Area thus does not affect all British universities in the same way. Some universities are more exposed to continental Europe than others. Those with a high proportion of EU students in their current cohort are concerned about tuition fee income. Elite universities with high research intensity and traditionally high success rates in European Research Council funding are more likely to worry about these sources drying up.

So, while the economic impact of Brexit on universities will vary, it is above all the lack of clarity about what the rules of the game will be in the future that is causing a lack of planning certainty. Those responsible at the universities are pursuing different strategies to mitigate the potential loss of income.

One strategy is to establish physical presences abroad. British universities have a long history of exporting higher education. One form of going abroad is through international branch campuses, which are now mainly located in countries such as Malaysia, Singapore, China or the United Arab Emirates. Some universities are following the government's "Global Britain" mantra: they are increasing their activities abroad and thus, through the international commercialisation of higher education, contributing to the further profiling of the British economy as a service exporter. Some are also seeking closer cooperation with the Commonwealth. By focusing on stronger links outside Europe, the potential loss of EU links could be compensated for.

Other universities have decided to set up branch campuses in the EU. These investments are intended as an "insurance policy" against the impact of Brexit. Lancaster University, for example, has announced the development of an international campus in Leipzig and sees a campus in Germany as a "natural extension" after previous branch campus investments in China and Ghana. Coventry University is planning a campus in the Polish city of Wroclaw.

In addition to UK campuses established on EU territory to teach EU and international students, several research-intensive universities have established collaborations, including physical presences in the EU. The University of Oxford has intensified its contacts with Berlin-based institutions. The Oxford/Berlin Research Partnership was established as a strategic response to Brexit and aims to create a legal structure that will allow Britons to continue to access EU research funding. The University of Oxford's new physical location in Berlin is intended to "support the intensive, direct collaboration that will be necessary for the partners to submit joint research proposals for EU funding programmes", according to a statement from the Berlin University Alliance.

Similar research collaborations are driven by research-intensive universities trying to access research funding from EU funds. The universities that have been particularly successful in accessing funds in recent years are the ones that are most active in shaping their close relationships with other EU countries. In this regard, Germany has become the partner of choice. The University of Cambridge entered into a strategic partnership with Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (Munich). King's College London and Technische Universität Dresden developed a "transCampus" initiative, and the University of Glasgow initiated a collaboration with Leuphana University Lüneburg.

The idea behind some of these initiatives may also be to create "continental outposts" where European Research Council funding can still be accessed by UK researchers. The success of these projects in avoiding loss of income is still uncertain. Previous examples of overseas campuses have proved difficult to manage and expensive to run. Thus, of all things, what is meant to be a solution to funding problems could end up being very costly. So are appropriate university strategies a sound response to the challenges posed by Brexit?

COVID-19: Danger for the Globalisation of Higher Education?

The corona pandemic in particular could now jeopardise the globalisation of higher education through campuses abroad, which originated in the UK, but also in other, predominantly Western countries such as France and the USA. International mobility has been repeatedly restricted as part of the pandemic response. How will this affect student mobility at branch campuses? How are the universities reacting? The new externally funded project "International Higher Education in Crisis: COVID-19 Impacts and Strategies", which will be funded through the Regional Studies Association's Small Grant Scheme on Pandemics, Cities, Regions & Industry and led by Jana Kleibert, will explore these questions. Some clues are already available.

On the one hand, branch campuses of international universities could provide an alternative for students who want to obtain international education degrees but are unable to enter the university's country of origin due to mobility restrictions. For example, in autumn 2020 - and perhaps even early 2021 - universities could recruit only domestic students who do not live too far from the branch campus. Similarly, they could provide an opportunity for international universities that have become dependent on the tuition fees of solvent foreign students to teach these students in their home countries. In Vietnam, VinUniveristy, in cooperation with the elite American university Cornell, wants to reach out to the more than 5,000 students who cannot travel back to Ithaca, New York in the new semester. They can now live on campus in Hanoi and follow their university's lectures in New York online. Similarly, future students who have been accepted to study at prestigious universities in the US will be given the opportunity to start their studies here instead. Some UK universities are likely to try to use their existing branch campuses in this way. Overall, this could also further accelerate the development of branch campuses as a resilience strategy in the future. According to a newspaper report, the Université Paris Sciences et Lettres, for example, sees the development of branch campuses as a possible future strategy to serve foreign students in the event of a future (pandemic) crisis.

However, some branch campuses have followed a different model: they depend on international physical mobilities of students and faculty and are thus particularly hard hit by the pandemic. Some function as mobility-enhancing hubs integrated into a larger international campus network. Students enrolling at the French business school ESCP, for example, move from branch to branch on a yearly or semester basis. Other offers follow a logic of educational tourism, targeting students in the university's country of origin who are interested in studying temporarily in a foreign country, as has been seen with some French campuses in Asia. In a global crisis that restricts freedom of movement across national borders, these branches need to rethink their business models.

Another trend that could be observed in HEIs after COVID-19 is a redefinition of mobilities to include online experiences. This can be seen, for example, in the Erasmus Virtual Exchange programme, a European online course programme that was launched in 2018 and in which around 8,000 students participated in 2019. Indeed, it remains to be seen whether the trend towards online learning will have a detrimental effect on offshore campuses, which are physical investments in a foreign country, or whether, on the contrary, online learning will become an integral part of the offshore campus structure and reinforce the development of transnational university campuses in the future.

Restrictions on international mobility, whether due to political dynamics such as Brexit or health crises such as the corona pandemic, are currently challenging universities oriented towards international branding in particular. As has been shown this year, several crises can reinforce each other: strategies in one crisis can be devalued by another crisis. But windows of opportunity for new ways of thinking also arise. And major trends such as the digitalisation of higher education are reinforced.