Main Content

The Struggle against Urban Decay in Contemporary Witness Interviews: A Short Research Report on Old Town Initiatives in the GDR

Working with eyewitnesses has a dubious reputation in historical research. For a long time, it was only considered a means of illustration. But personal recollection can also serve as a source of important insights – especially in combination with and in contrast to written sources. IRS historian Julia Wigger used this combination of methods in her research on old town initiatives in the GDR. Here she shows how the two types of sources complemented each other.

The contemporary witness as the natural enemy of the historian – this more or less serious bon mot appears sooner or later when working with contemporary witnesses in historical research projects. There is no denying the methodological challenges in dealing with self-conducted interviews: Many studies have appeared on the relationship between individual memory and societal remembrance in the humanities and social sciences. Among other things, the fluidity and inadequacies of memory have been pointed out. Scholars have also repeatedly emphasised the subjectivity of oral reports. Researchers have also reflected on the importance of the person conducting the interview, which should not be underestimated. The setting, the manner and the way the questions are asked have an immense influence on the answers that are formulated. In addition, the use of eyewitnesses for the sole purpose of providing evidence or authenticity has often been criticised. Yet despite all the methodological challenges, a large number of research projects have now impressively demonstrated the added value of working with eyewitnesses, also for research on GDR history. Particularly when it comes to everyday and social history, it is not always possible to find (complete) written records on the issues at stake.

Focus on the Urban Population

It is therefore hardly surprising that the joint research project “Urban Renewal at the Turning Point” (“Stadtwende” - for details on the project, see p. 13) also aimed to include contemporary witnesses from the very beginning. Since 2019, I have been focusing on the urban population in the collaborative project, which deals with the handling of historical building fabric in the GDR and East Germany. My task in the project is to ask how citizens reacted to progressive decay and planned demolitions. I am also writing my dissertation on this topic, which is in the field of historical studies at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and is supervised by Christoph Bernhardt and Heike Wieters.

One of the starting theses was that decay and vacancy not only provoked anger and migration to the new development areas, but also led to a social activation. In order to examine this, I focus on the so-called old town initiatives. Similar to peace, environmental or women's groups, the old town initiatives were an organised form of engagement that began to emerge in the mid-1980s. Citizens joined together in groups to work for the historical building fabric. To do this, they picked up the tools and carried out repairs themselves, they wrote petitions or organised exhibitions. Often they integrated themselves into state structures such as the Kulturbund or the local housing district committees in order to avoid criminalisation. My research interest in the Old Town initiatives is strongly oriented towards social history and less towards architectural history. The focus is on questions about the emergence, composition, practices and development of the groups beyond the social upheaval of 1989/90.

It was already known at the beginning of the project that there was an important and extensive corpus of sources in the Archive of the GDR Opposition of the Robert Havemann Society that documented the work of the old town Initiatives in detail. The corpus was created by IBIS, the Information and Advisory Institute for Civic Urban Renewal, and documented the activities of the old town initiatives since 1990. In addition, I assumed that I would find further written records in the state archives as well as in the city museums and archives. Nevertheless, it was soon clear that interviews would be another important building block for my doctorate. The interviews I conducted did not follow the traditional oral history approach, i.e. letting people tell their life stories, but were supported by a previously prepared guideline that was used in an adapted form for each interview. The questions to the interviewees were directed at their commitment to the historic building fabric. I was also interested in how the actors assessed their commitment retrospectively or what significance they attributed to the 1989/90 caesura. In some cases, the interviewees also gave me written materials from private collections, which were then returned or – after consultation – handed over to relevant archives.

More than just Vivid Anecdotes

Conducting the interviews was the most entertaining part of the process. The transcription and evaluation of the interviews, which usually lasted about one and a half hours, turned out to be time-consuming but at the same time necessary work. Only in this way is it possible for me to relate the interviews to each other, but also to written sources and the research literature, and to classify them.

Among other things, the interviews give personal impressions of how the interviewees perceived life with and in the historic building fabric. Mr W. from the Saxon town of Pirna, for example, recalled:

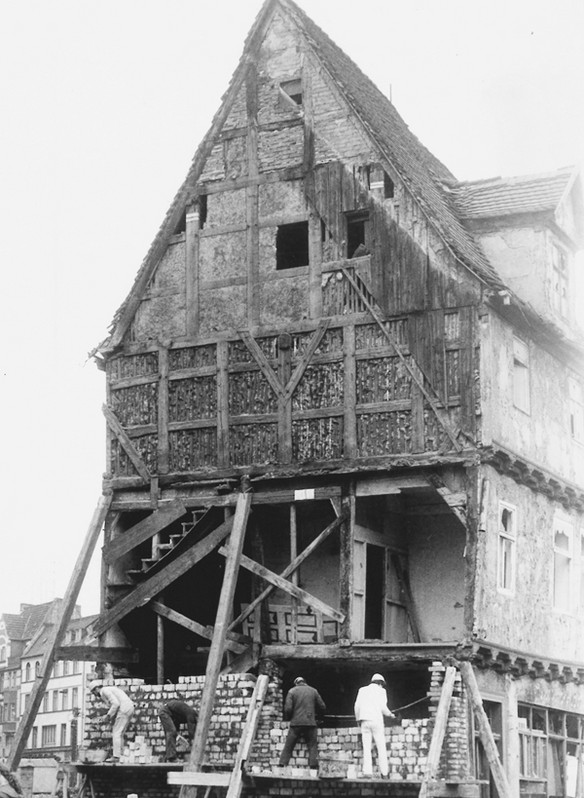

“Well, it was obvious in the 1970s and then very strongly in the 1980s that the houses were really deteriorating in the last decade of the GDR era. I myself lived in the old town at that time and improvised with craftsmen, friends and acquaintances. So we repaired gutters ourselves. We also closed up holes with roofing felt. [...] So we were forced, if we wanted to stay in the old town, to save a lot of things through repairs and improvisation. However, one house after the other was closed down, bricked up, nailed shut, and it was a gruesome sight to walk through the town on a gloomy November day in the mid-1980s.”

The quotation vividly illustrates the condition of the old towns. However, the evaluation of the interviews must not stop at using descriptions that impressively underline what has already been proven in scientific research with sober figures. It is also a matter of taking the interviews seriously as a source and deriving new insights from them.

A concrete example can show the added value of the interviews particularly well. For example, I am dealing with the question of when supra-regional contacts existed between the Old Town initiatives. However, this can hardly be answered from the written sources alone. This is because supra-regional meetings are only documented in detail from 1990 onwards. In the interviews conducted – and also in the background discussions that were not recorded or transcribed – an event at the Academy of Arts of the GDR was mentioned again and again, which called for saving the old towns on 11 December 1989. Only very brief references to this event can be found both in the contemporary press and in the literature. Details about the content or participants, which would have allowed conclusions about the size and significance, are completely missing. Without the advice of my interlocutors, I would probably have underestimated the significance of this event. In addition, a folder with the collected materials from the event turned up at one of the witnesses' homes. This collection of material, together with the interviews conducted, made it possible to reconstruct the speakers and their contributions and to identify the event as an important milestone in the supra-regional networking of the old town initiatives. A classification that would not have been possible solely on the basis of the available written sources and existing literature.

Take Contradictions Seriously

But it is not always easy to integrate narratives with the findings from written records. For example, the search for contemporary witnesses who could tell me something about the work at the Round Table of Citizens' Initiatives in the Ministry of Construction or the supra-regional meetings of the Old Town Initiatives organised by IBIS in the early 1990s proved difficult. Yet both the Round Table at the Ministry of Construction and the IBIS meetings are well documented in the written records. With the help of attendance lists, I was even able to keep track of who had taken part. However, many of those who were contacted could not remember having been there, or they remembered it only very vaguely and in retrospect attributed a subordinate importance to the events for their engagement. This was in contradiction to the importance of these supraregional meetings that I had assumed, since they were well and extensively documented in the IBIS inventory and proved the diversity of the topics discussed as well as the initially large participation of numerous old town initiatives. However, non-remembrance must also be taken seriously. On the one hand, this can be interpreted against the background of the many parallel changes and developments in 1989/90. At the same time, the non-remembrance must also be seen against the background of the further development of the old town initiatives. Already at the beginning of the 1990s, many old town initiatives stopped their work again or focused their commitment more on their own city. The number of participants in the supra-regional IBIS meetings also declined. It is therefore not surprising that in retrospect the supra-regional networking is not considered to have played a major role, as it has not been able to establish itself in the present. At the same time, it cannot be concluded from these personal assessments that the supra-regional departure was not successful or not important.

The examples given here are examples of how I use the self-conducted interviews in my dissertation. I regard them as sources that stand alongside the written records, and just as these must be subjected to careful source criticism. With this approach, the interviews provide me with information about the motivation and self-image of the activists, for example, about which there are hardly any references in the written sources. But the interviews also open my eyes to details, they repeatedly point out connections that have not been written down and give me new ideas for my research in the archives.

Oral history is so beautiful because it comes with so many problems, as the Austrian historian Albert Lichtblau once put it at an event. That is certainly another of those half-joking sentences, but I would agree with him: The methodological challenges are complex, the time required is immense, but the added value for research should not be underestimated and the resulting encounters are definitely worth the work.