Main Content

Focussing Data-Driven Knowledge Production in Planning

Comment on Debate Surrounding "Polyrationality"

In planning research, a debate is unfolding about the role of truth. The key question is: should planning science accept that several subjective truths exist side by side ("polyrationality")? Or must planning and planning research be based on a binding, scientifically proven truth? For IRS planning researcher Christoph Sommer, the key lies in a critical approach to data.

How do you plan when people believe in alternative facts and actually live in alternative worlds? This is a question that concerns planners. You don't even have to think about climate change deniers and their political representatives. The slow reaction to the obvious need for socio-ecological transformation may also only be explainable to some as the result of a self-righteous denial of reality. In the "post-factual age", the question of how planning can deal with multiple truths is obviously urgent - and accordingly also the subject of discussions on planning theory. Christoph Sommer has commented on the debate in the journal "Spatial Research and Planning".

The starting point for the controversy over how to deal with multiple truths in planning was an article in the specialist journal "European Planning Studies". In it, planning scholars Benjamin Davy, Meike Levin-Keitel and Franziska Sielker (2023) discuss the theoretical and practical handling of the current "brutal plurality of truths". Davy et al. propose taking "polyrationality", i.e. the acceptance of different coexisting truths, seriously as a mode of planning practice. They argue in favour of a considered pluralistic approach to planning theory. The political scientist Gerd Lintz (2023) took the aforementioned article by Davy et al. as an opportunity to urgently warn against a kind of postmodern relativism in "Spatial Research and Planning" . According to Lintz, the "broad concept of truth and knowledge" is problematic because, among other things, it tends to devalue intersubjectively verifiable knowledge, i.e. the core of scientific knowledge acquisition, and thus makes interdisciplinary cooperation with the natural sciences, engineering, law and economics more difficult. Hence, while some advocate questioning both theoretically and practically how (supposedly objective) planning truths are created, Lintz emphasises the dangers of an overly broad concept of truth and knowledge.

In his commentary on this dispute, Christoph Sommer begins by pointing out its parallels with the "science wars" of the 1990s. The latter were - to put it very simply - a dispute between the sociology of science and the natural sciences. The former questioned the nature of scientific truth, while the latter defended itself against postmodern relativism. In his commentary on the debate, Christoph Sommer starts from the assumption that (in the words of sociologist Bruno Latour) "everyone, both scientists in the 'hard' and the 'soft' sciences, politicians and users, [...] have a legitimate interest in gaining as realistic an assessment as possible of what the sciences can and cannot do". Instead of conducting a fundamental debate in the style of a trench war between postmodern theorists on the one hand and "hard" scientists on the other, he argues in favour of looking at how planning-relevant knowledge is produced and what significance it has. In concrete terms, this means looking at data-supported knowledge production, which increasingly prepares, structures and potentially anticipates planning decisions.

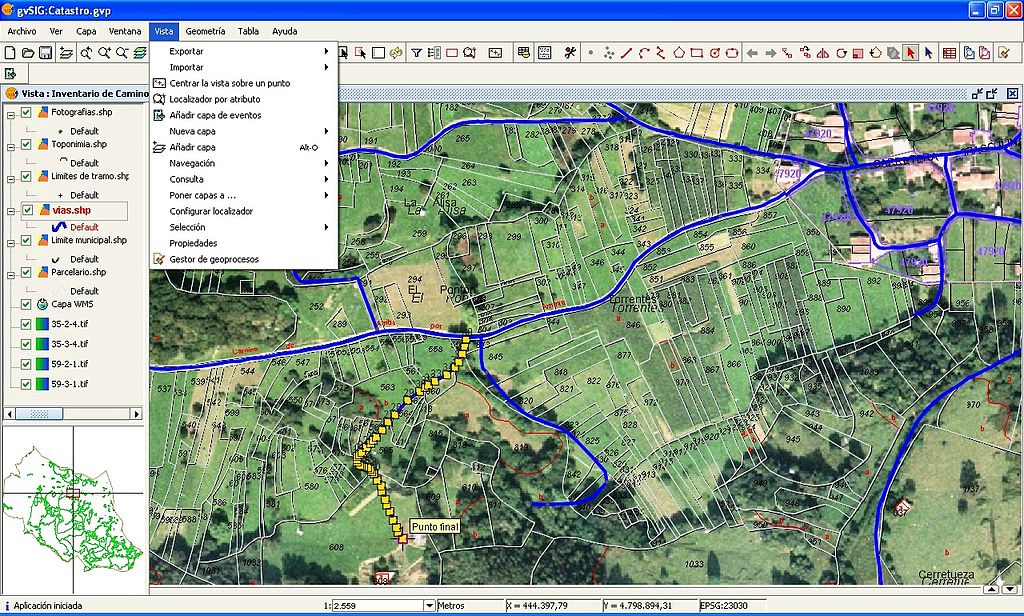

In Christoph Sommer's view, a radical belief in the scientific rationality inherent in data and its action-guiding effect ("follow the science") would have the potential to depoliticise planning. Ultimately, it would only be a matter of "rational" modelling of competing uses of space. Planning decisions would be legitimised primarily "from the data". What is needed, however, is a planning policy negotiation of spatial development goals orientated towards the common good. This is why a critical examination of various data modelling methods produced by different disciplines and stakeholders is needed. This approach offers a double connectivity: on the one hand, planning practice recognises the problem of being confronted with different rationalities of thought. In Sommer's opinion, there is potential here for fruitful exchange and joint research with practitioners (transdisciplinary research). On the other hand, a dialogue on data-based knowledge production can also be conducted well with representatives of other scientific disciplines.