Main Content

Growing inequality On the Social Situation in (East German) Large Housing Estates

Large housing estates exist in both East and West Germany. However, their starting points, their lines of development and the social composition of their inhabitants differ significantly in both parts of the country. Whereas large housing estates in West Germany were from the beginning focal points of immigration and inhabited by predominantly low-income households, the “Plattenbau areas” in East Germany underwent a dramatic transformation: From popular and socially largely homogeneous residential neighbourhoods to places of out-migration and finally to centres of renewed immigration. In this process of change, the socio-spatial inequality in East German cities overtook that in West German cities.

Since the 1960s at the latest, both in West and East Germany, large housing estates were built in industrial multi-storey construction technique to create space for the rapidly growing population in the post-war period. While large housing estates in West Germany, such as Cologne-Chorweiler, were seen as a less attractive form of housing and were often home to an above-average number of “guest workers” – as immigrated workers used to be called – and their families, the large housing estates built in prefabricated slab construction in the East, such as Cottbus-Sandow, were popular and were inhabited by all social classes. On the one hand, there were urban planning reasons for this, because the old towns in the east were hardly modernised and suburban housing estates were not built. On the other hand, socio-spatial inequalities could hardly arise because the GDR as a whole hardly allowed for economic inequalities.

Today, the situation is different. As my colleague Stefanie Jähnen from the Social Science Research Center Berlin and I showed in 2018 in our study “Wie brüchig ist die soziale Architektur unserer Städte?” (“How Fragile is the Social Architecture of Our Cities?”), the (large) cities in eastern Germany have particularly deep socio-economic trenches, which have also deepened particularly strongly in recent years. The extent and dynamics of social inequality in the East even proved to be greater than in West German cities – a finding that caused quite a stir. While the few existing studies still described the social distribution of the population in the eastern German cities as socially homogeneous in the mid-1990s, the eastern German cities we studied already showed a higher spatial unequal distribution of poverty (segregation) in 2005, measured by the proportion of households receiving SGB II (unemployment benefit II), than the western German cities. Moreover, the residential neighbourhoods of the eastern German cities are becoming increasingly unequal over time, whereas this is hardly to be observed in western German cities. Poverty is increasingly concentrated in large housing estates. Poverty rates in the large housing estates themselves have not risen over the last 15 years. It is rather the case that they have remained constant (high) despite the very good economic development, while they have fallen sharply in the other city districts. Most recently, poverty rates of 50 % among children in large housing estates in eastern Germany were not exceptional.

Some differentiation is in order, however, because the findings are not homogeneous. The study “Berliner Großsiedlungen am Scheideweg?” (“Berlin Large Housing Estates at the Crossroads”) by the Kompetenzzentrum Großwohnsiedlungen e. V. from 2021 shows that the social situation in West Berlin's large housing estates is even more strained than in East Berlin. Child poverty (the proportion of children in families receiving transfer payments) is 50 % in the large housing estates in West Berlin, 37.5 % in the large housing estates in East Berlin and 22.6 % outside the large housing estates. What East and West Germany have in common is that it is precisely the housing estates that are particularly hard hit by poverty that are decisive for the extent of social inequality overall. A decisive difference between East and West, however, is that the large housing estates in East Germany are home to a significantly higher proportion of the total population. Systematic differences between large housing estates and other neighbourhoods therefore have a greater impact on city-wide measures of inequality in the eastern German cities.

Moving West, Suburbanisation and Inner-City Redevelopment

How did the development described above come about? As a result of the Peaceful Revolution, from 1989 onwards three overlapping migration trends from the large East German housing estates took place. First, a strong exodus to West Germany be-gan due to rising unemployment. This mainly affected large housing estates near industrial combines (e.g. Halle-Neustadt or Hoyerswerda). The second wave of the exodus began in the mid-1990s as a process of catch-up suburbanisation, “in the course of which the flywheel of social segregation gains its actual momentum”, as urban and regional sociologist Carsten Keller writes. The process of suburbanisation set in so late because it was only after a few years that significant assets had been accumulated in East Germany that made it possible to buy a home on the outskirts of the city. In addition, the key interest rate of the German Bundesbank was around 8 % until the beginning of 1993, which made borrowing unattractive, and then decreased to 2.5 % by the beginning of 1996. The group that moved to the outskirts of the East German cities during this period were mainly financially strong family households from the prefabricated housing areas. Those households that could not afford another form of housing were left behind. Increasing vacancies and loss of purchasing power made services, trade and infrastructure in the large housing estates uneconomical and they disappeared. As a result, the social segregation in the prefabricated buildings became a trigger for further exodus. It was further exacerbated by the influx of people receiving transfer payments into the large housing estates in East Germany.

Parallel to the construction of single-family housing estates in East German suburbs and villages, the old quarters in the inner cities were increasingly refurbished. The comprehensive redevelopment began somewhat later and was less dynamic than suburbanisation. Nevertheless, migration to redeveloped inner city locations is another factor that can explain the high degree of social segregation in some eastern German cities. Precisely because many East German cities were less destroyed in the war than in the West (with the exception of Dresden and Magdeburg), and the old towns were not affected by architectural fashions and experiments, the historic building fabric has been preserved. Today, the redeveloped city centres are sought-after locations. The large housing estates, on the other hand, which are often located on the outskirts of the city (e.g. Erfurt-Nord, Schwerin-Großer Dreesch, Leipzig-Grünau, Halle-Neustadt), shrank and became increasingly segregated.

Within the large housing estates, the social situation differs once again depending on the year of construction: the large housing estates built before 1977 are less affected by poverty, but more affected by ageing (proportion of over 65-year-olds) than the large housing estates built after 1977. The reason for this is not to be found in the structural quality of the building stock, but rather in the phase of life of its residents at the time of the Revolution of 1989: Those who had moved into a flat before 1977 typically had school-age children in the early 1990s, which made a move to the West seem impractical, and (almost) adult children in the late 1990s, which in turn made moving into a home less attractive. Younger large housing estates were typically occupied by younger families, who were the most active groups in moving away. Thus, newer neighbourhoods (e.g. Rostock-Groß-Klein, Erfurt-Berliner Platz, Halle-Silberhöhe or Schwerin-Mueßer Holz) were particularly hard hit by people moving away and becoming segregated.

The older large housing estates by contrast (e.g. Chemnitz-Yorckgebiet, Magdeburg-Brückfeld, Erfurt-Johannesplatz or Jena-Lobeda-West) have so far remained more socially stable, additionally supported by the fact that old-age poverty seems to be a much smaller problem in the East German large housing estates than in West German large housing estates. The lower rate of old-age poverty in East Germany is due, on the one hand, to the high proportion of women who did not work full-time in West Germany. As a result, the old-age poverty rate of women is higher in the West than in the East. In addition, there is a disproportionate number of migrants living in the large housing estates in western Germany, who were more likely to be affected by unemployment, but more importantly, some of them have not acquired full pension entitlements. In the East German prefabricated housing estates, there were hardly any people with a migration background until 2014. Despite being more socio-economically stable, however, older East German estates will experience a significant change in the coming years due to the death of first-time residents. Starting in 2015, immigration became a major driver in repopulating East German large housing estates.

Large Housing Estates as Arrival Neighbourhoods for Migration

Until a few years ago, the proportion of people with a migration background or without German citizenship was the aspect that differed most between eastern and western German large housing estates. Before 2014, the proportions of foreigners in the large housing estates of the large eastern German cities were nowhere above 6 % and only in a few cities were the proportions of foreigners in the large housing estates higher than in the rest of the residential areas. This changed between 2014 and 2017, i.e. during a phase of pronounced refugee migration to Germany. As a result, the economically weakest large housing estates in eastern Germany became focal points of immigration.

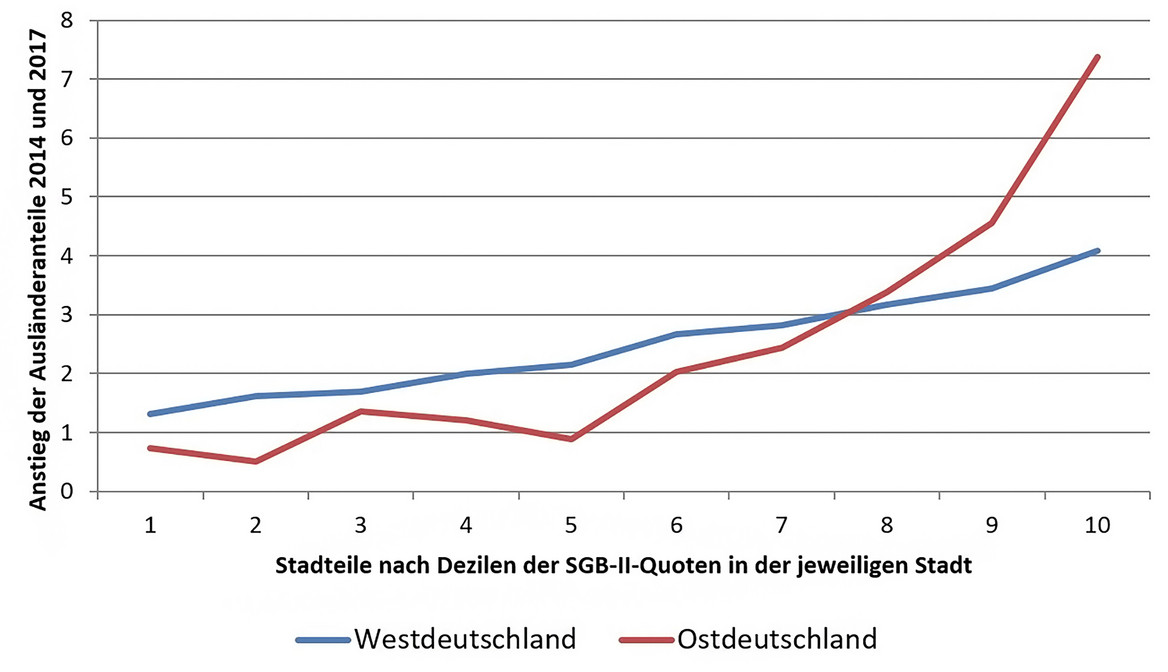

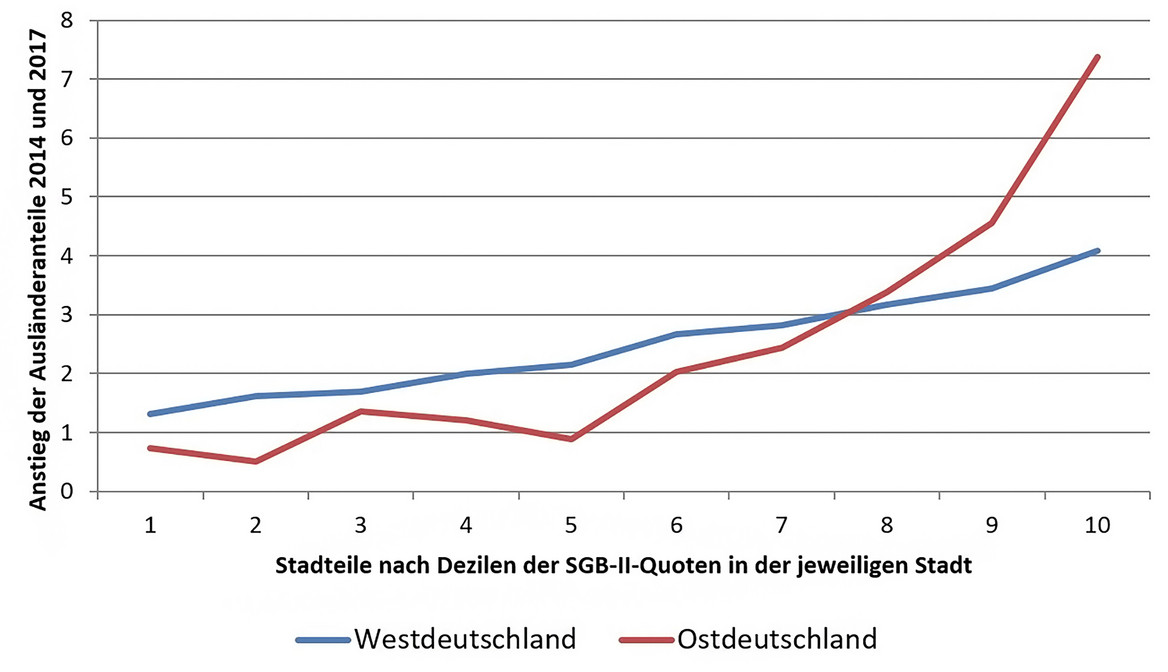

As can be seen in the figure, the proportions of foreigners in the neighbourhoods of 86 cities studied changed between 2014 and 2017. It can be seen for the western German cities that the proportions of foreigners in the most socially privileged neighbourhoods (1st decile, i.e. the highest-income 10 % of all neighbourhoods, measured against the average of their respective cities) increased the least, by 1.3 percentage points, and in the most socially disadvantaged neighbourhoods (10th decile) the most, by 4.1 percentage points. This correlation between immigration and social situation can be observed even more strongly in the eastern German cities. While the proportion of foreigners in the socially privileged to middle locations has only risen by about one percentage point, a very strong increase is evident from the 6th decile onwards. In the 9th and 10th deciles, in which the large housing estates are predominantly found, the proportions of foreigners rose by 4.5 and 7.3 percentage points respectively. In this respect, it is precisely the most socially disadvantaged neighbourhoods that have to make the greatest integration effort. A large part of these developments can be attributed to the fact that the newly immigrated, predominantly low-income groups were able to settle primarily in areas where vacancy rates were high. In eastern Germany, these were particularly large housing estates on the outskirts, for example southern Halle-Neustadt and Schwerin-Mueßer Holz. Where there were fewer vacancies (e.g. in Jena, Rostock or Potsdam), the foreign influx was less socially selective.

Nevertheless, the large housing estates in West and East Germany still differ greatly from each other in terms of their ethnic composition. Looking at the large housing estates in West Berlin, for example, the proportion of people with a migration background was 49.4 % in 2018. The East Berlin large housing estates were far below the Berlin average with a share of 24.9 %. But nowhere has the increase in recent years been as strong as in the East German large housing estates.